Road Raging - Top Tips for Wrecking Roadbuilding

Chapter 15 - Legal Issues

When entering into a direct action campaign

there are many aspects of the law you will need to learn. As people's liberty

could be at stake, it is dangerous to think that the law does not matter, or

is irrelevant. Much of what we do brings you into contact with the police, who

will nick you for existing if they want to. The campaign and those in it have

a responsibility to give people legal support.

Legal stuff can be boring and frustrating, and sometimes seems pointless,

but it is an essential facet of any campaign which wants to survive and

thrive. It can involve anything from finding good and sympathetic lawyers,

encouraging people to act as witnesses for each other, helping each other

through court cases, knowing your rights, through to suing the police.

This chapter may appear daunting and there is a lot to know. However, there

are lots of groups and lawyers out there who can help your campaign. We have

tried to cover things as extensively as possible, but this is not a definitive

guide. At the time of writing all the information included in this section is

as correct as we can get it - we've checked it with several lawyers - but the

law is continually changing. Also, this chapter is based entirely on the law

as it stands in England and Wales. There are differences in other parts of the

UK. There are two different broad areas of law, civil and criminal. Briefly,

civil law covers disputes amongst individuals who can go to the County or High

Court to sort it out. Criminal law is where the State (via the police and

their solicitors, the Crown Prosecution Service) can take you to the

Magistrates or Crown Court, for some "wrong" against "society". There is often

overlap between the two, especially when squatting.

Wildlife And Countryside Act 1981

The Wildlife and Countryside Act

1981 (WCA) makes it an offence to deliberately injure certain wildlife (e.g.

bats and birds), and in certain circumstances their homes, particularly those

of nesting birds. (Badgers also have their own special protection under the

Badgers Act 1992). Unfortunately, there are so many exemptions incorporated

into this legislation that it makes it almost toothless against developers and

Government. The Act creates various supposedly protective designations for

areas of land, eg. Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). Damage to

protected areas generally do not count if planning permission has been

granted, or the destruction is caused by a government body.

English Nature is supposed to enforce this legislation in England, but they

are about as effective a watchdog as a kitten. Although they do have some good

environmentalists amongst their ranks, they rarely put up a robust opposition

to government projects, simply because they are State funded. If you see

anything which is a breach of the WCA, it is worth trying to do something

about it. If it is a private company you are opposing, English Nature may be

more inclined to act. They are a lever worth pressurising, but never rely on

them. There are separate bodies in Wales, Scotland and the north of Ireland

with similar functions.

European Law

There are several European Directives incorporated into

British law that are supposedly designed to protect the environment, and all

EU countries theoretically have to obey them. These include the Environmental

Impact Assessment Directive (all major schemes should have a thorough EIA),

the Habitats Directive and the Birds Directive. These Directives require the

designation of protected areas. For example, the Habitats Directive creates

Special Areas of Conservation (SACs), and the Birds Directive creates Special

Protection Areas (SPAs).

If you believe that your government has broken a Directive, you will have

to make a complaint to the EU and then follow it up. It will take months or

years as the wheels of bureaucracy turn very slowly. Don't expect "Europe" to

come rushing to your aid - political deals and back-handers are rife. However,

complaints may be worth making for the propaganda value. Get in touch with

Friends of the Earth or ALARM UK for advice on complaints to the EU

Environment Commission.

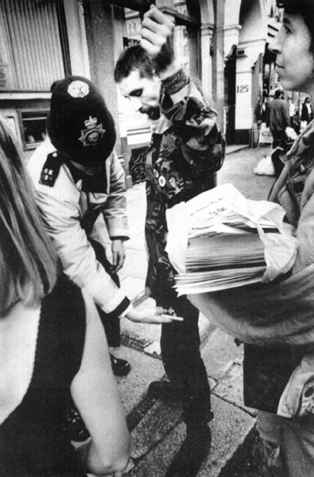

Public Processions And Assemblies

Public processions and assemblies

are subject to legal restrictions, most notably the Public Order Act 1986

(POA), sections 11 - 16, and the Criminal Justice and Public Order 1994 (CJA),

sections 70 - 71. The police can ban them, impose conditions and arrest you if

you refuse to comply.

Advance notice of processions is required by law, under the POA. The notice

is required in writing at the local police station, ideally at least 6 clear

days before the procession, and should include routes, times, and

names/addresses of organisers. The notice should be given as soon as is

"reasonably practicable" - for truly spontaneous demonstrations a phone call

at the last minute maybe acceptable. Failure to give notice doesn't mean the

march cannot take place, but the organisers and participants could possibly

face criminal charges and fines (if they can prove who the "organisers" are!).

In practice, your local police might not enforce this. The police can ban a

procession by applying to the local authority for an Order. Breaking this

Order is a criminal offence.

If the march is permitted, the police have the power to impose conditions

(e.g. numbers of stewards, no stopping etc.) and specify routes for the

procession, at any time. It is an offence for organisers and participants not

to comply with the conditions (max. sentence 3 months prison and / or fine for

organisers, fine only for participants).

Public assemblies (static demonstrations of over 20 people in the open air)

do not need an advance notice and the police have no powers to ban them,

although they can impose on the spot conditions (duration, numbers, place) if

serious disruption or damage to property seems likely. Criminal charges can be

brought against those not complying with orders (max. sentence 3 months prison

and / or Level 4 fine).

Under the CJA sections 70 - 71, the police have massive powers over

"trespassory assemblies". They may apply to the local Council (or in London,

to the Home Office) for a ban if they believe that a trespassory assembly is

planned and may result in either serious disruption to the life of the

community, or there will be significant damage to land / building / monument

of historical, architectural, archaeological or scientific importance. The ban

affects all trespassory assemblies, lasts up to 4 days, and applies to a

radius of 5 miles from a specified centre. If you know the assembly is

prohibited, it is an arrestable offence to organise, take part in or incite

others to take part in it (max. sentence 3 months prison and / or fine). The

police have the power to stop or direct people not to proceed in the direction

of an assembly within a 5 mile radius, if they believe that they are on their

way there. It is an arrestable offence to knowingly fail to comply with the

order (Level 3 fine).

Squatting Land And Buildings

Most of squatting is covered by the civil

law. The CJA has changed the law and made squatting more difficult, but not

illegal. The new method is described separately below under CJA evictions.

However, the pre-CJA procedure is still the most commonly used, so we will

describe that first. Theoretically the police should not get involved - unless

you cause damage, have lots of vehicles or refuse to move if an Interim

Possession Order (IPO) has been obtained.

When you squat someone's land or building, you are trespassing on

their property. The usual way to get you out is for the owner to go to the

civil courts to obtain a Warrant or Writ of Possession and instruct bailiffs.

It is time consuming and expensive for the owner, but has existed like that

for centuries to protect those who have a legitimate claim to a property from

being kicked out by unscrupulous and powerful people.

When you squat someone's land or building, you are trespassing on

their property. The usual way to get you out is for the owner to go to the

civil courts to obtain a Warrant or Writ of Possession and instruct bailiffs.

It is time consuming and expensive for the owner, but has existed like that

for centuries to protect those who have a legitimate claim to a property from

being kicked out by unscrupulous and powerful people.

A totally different set of laws apply if you are squatting somewhere that

someone is already living in. You will get kicked out almost immediately. So,

the old Sun-style stereotype of squatters moving in when a family goes on

holiday is a load of rubbish. People usually squat a building that has been

left empty for ages and is going to waste.

The usual pretext for the police getting involved with these procedures is

if there has been damage done to the property, e.g. to locks, doors and

windows, or burglary (ingredients being trespass and criminal damage, or

theft, including that of electricity), or if violence is used to get in

(Section 6 of the Criminal Law Act 1977), or if a Breach of the Peace has

occurred.

Criminal Law Act 1977 - Sections 6 and 12

You have some protection from forced eviction under the Criminal Law Act 1977

(CLA). Section 6 of this Act makes it an offence to "use or threaten violence

to secure entry to any premises when it is known that there is someone present

on the premises who is opposed to the entry". The penalty is up to 6 months

imprisonment or a Level 5 fine (for fine levels, see below). Someone must be

present at all times for Section 6 to apply. Most of the time squatters will

put up a "Section 6" notice saying all of this (an example of one is in the

Appendix). Putting one up does not make you immune from attack, but it will

give you extra weight if you go to court about a forced eviction. You can say

that you adequately warned your attackers that they were in breach of Section

6 of the CLA.

Many camps have created a physical boundary to define their area and asked

that this be respected by the security guards. In a long term campaign you

must follow up any illegal forced eviction or illegal entry onto your

property, or the enemy will do it again. This will involve trying to persuade

the police to prosecute (well, it is worth a try), or by giving information to

the Crown Prosecution Services (CPS) and magistrates and asking them to

prosecute.

Section 12 of the CLA gives definitions of the terms used in the Act,

including Section 6. This is especially relevant for squatting land. The DoT

in Britain have disputed the fact that Section 6 applies to camps saying that

the definition of "premises" given in Section 12 does not cover camps. If you

read Section 12 it clearly says that premises means "any land ancillary to a

building" and "any ancillary land thereto". It also defines buildings as "any

structure other than a movable one, and any movable structure designed or

adapted for use for residential purposes". Make sure that police, bailiffs and

security know you will collect evidence of any breaches of Section 6, and will

be prepared to argue this out in court.

Eviction proceedings and fighting it in court

You may choose to fight the eviction through the courts. This may be as you

have a genuine case, or it may be that you just want to delay the eviction and

cost them more money. If you can delay them getting an Order in the courts you

can sometimes really mess up their plans and schedules.

When you squat a piece of land or building you may wish to notify the

owners by post or fax to remind them of Section 6 of the CLA, so they can

instruct their agents and security guards to stay away. This has pros and

cons. Give them the minimum info to avoid helping them draft their eviction

papers. This will give you more evidence in court to prove you have been

illegally evicted, and it may worry them into carrying things out

correctly.

You will often know when they are making moves to evict you. They will

probably come round to your camp (or squat) and serve you with a Notice to

Quit. This will usually give you 48 hours to leave. After this time, they will

come back and formally ask you to leave. They will probably film all this as

proof. They will then apply to the courts to get you evicted. You will next

receive a Summons to court. If they do not have any of your names the Summons

will be against "Persons Unknown". It has to be served properly, in a sealed

transparent wallet and affixed to your door or attached to posts hammered into

the ground. See Appendix for an example of an eviction Summons.

You will have to decide if you then want to put any effort into contesting

the eviction in court. At least one person will have to give them a name (real

or false) to do so. This will, at the very least, make them work for their

eviction. You can, if you put some thought and effort in, delay them for

months. This was achieved in the case of Stanworth Valley along the route of

the M65 in 1995. It took them several months to get their Possession Order,

and valuable time was bought to build even more tree houses and make sure that

those woods saw another Spring.

If you can get a lawyer to help you, then all the better. You may even be

able to get Legal Aid and have them represent you, although this is rare and a

lawyer will be limited in what (s)he can say. If you don't get representation,

you will have to go and defend yourself in court. You may be able to get an

adjournment. Grounds for an adjournment might be: need more time to prepare

complicated case, court case to be held nearer to (poor) defendants, or

technical irregularities in the proceedings. Defences could include: pending

case in the European Courts, challenging their ownership of the land, if you

had permission to be there, or you have been squatting there for more than 12

years. If the judge does not accept your defence, they will probably grant a

Possession Order "forthwith" (at once). The Order can last for 12 years, if

not used.

Appeals

An appeal can buy you even more time. During anti-road protests, the DoT have

never evicted whilst an appeal is pending. It really would not look good for

them if, when the appeal came to court, they had to admit that they had

already cleared the area. In the High Court, you can appeal to a Judge against

the decision of a Master. You must do it within 5 working days of the

decision. There is a fee of £20 (if you have evidence of being on the

dole they should waive you the fee). There is also a lot of paperwork to be

typed and submitted. You will get a fresh hearing. Contact squatter groups

(see Chapter xx) or a lawyer for advice.

In the County Court, you can appeal to a Judge about the decision of a

District Judge, but not against the decision of a Recorder or an Assistant

Recorder. You must do it within 14 days of the decision and there is, again,

the £20 fee. The Judge will review the decision, but you will not

necessarily get a fresh hearing. You can go further and appeal to the Court of

Appeal, but this has risks: huge court costs and making bad law.

Costs

If you lose, you will almost certainly have costs awarded against you. A

lawyer would advise you against taking legal action because of this risk. In

the past, however, they have never attempted to get costs back as they know we

can't and won't pay.

The Eviction

The Possession Order enables a Warrant or Writ of Possession to be issued,

instructing bailiffs or Sheriff's Officers. This usually takes at least a few

days. If you are a named defendant, you can request in writing any documents

in the court files relating to the enforcement of the Possession Order.

Regularly doing this could give you a tip off about the timing of the

eviction. If the court officials refuse to allow you to inspect the file, you

should point out to them Order 63 Rule 4 in the High Court, and Order 50 Rule

10 in the County Court. For more on this under-used technique, see Basic Law

for Road Protesters (Chapter xx).

You may be "privileged" enough for the Sheriff's deputy, the Undersheriff,

to turn up at the eviction or it may be just their certified, sworn-in

bailiffs. It will be their duty to ensure that the Writ or Warrant for

Possession is enforced. They should have the Writ or Warrant when they come to

do the eviction. Ask to see it (if you are not locked onto the roof or up the

trees!) The Bailiffs are allowed to use reasonable force to remove you, and

resisting them or the Sheriff is a criminal offence (see below).

Returning to land

If a piece of land or property has a Writ or Warrant of Possession on it and

you return to it, you may get immediately evicted as they last for a year.

They just have to obtain a Warrant of Restitution from the courts (without

notifying you) and then come and evict you without warning. So if you intend

to re-squat a piece of land be prepared for this and get out of reach!

CJA Evictions

Under the CJA (sections 75 - 76), a new, faster eviction process has been

created, which only applies to buildings. It is very similar to the process

described above except the owner can apply for an Interim Possession Order

(IPO) before a full eviction hearing. If an IPO is granted, you commit a

criminal offence if you remain there, or return, after 24 hours has elapsed.

This new law is particularly unjust, as even if you have a good case for the

actual hearing, you may be already out of your squat (and possibly arrested).

They have to serve you with the Summons for the IPO hearing within 28 days of

them knowing you are in occupation, not from when you moved in. You will be

summonsed to court, often with very short notice. The Summons will have a

blank affidavit attached which you must complete and return to be able to

attend court. At the hearing, you are not allowed to speak unless the judge

invites you to, or asks you a question. However they usually do. If the judge

grants the order, the IPO can be served, usually within 48 hours. If you are

still there within 24 hours, the police will do the eviction without bailiffs

and can arrest you.

Also, under sections 61 - 62 of the CJA (the "travellers" sections), a

senior policeman can instruct trespassers to leave if they have already been

asked to leave by the owner of the land or their agent, and either the

trespassers have "caused damage" to the land, or "used threatening, abusive or

insulting words or behaviour" towards the owner or agent. They can also make

you leave if you have six or more vehicles on the land. The trespassers can be

arrested if they refuse to leave and vehicles can be impounded.

This is only a very brief summary of laws surrounding squatting. If you

plan to squat either land or buildings, get in touch with some of the

excellent squatting organisations around (see Chapter 16).

Some Relevant Police Powers

The police often exceed their legal

powers, relying on your ignorance of the law and their ability to intimidate.

Their powers are set out in a series of Acts, most of it being in the Police

and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (known as PACE). The following is a summary of

some of their actual powers and is not exhaustive.

The police have extensive powers to stop and search people, vehicles and

property, before arrest, in a public or private place and seize possessions.

Generally speaking, the police may stop and search people and vehicles where

they have reasonable grounds for suspecting that they maybe carrying firearms;

drugs; stolen goods; articles for use in thefts, breaking into vehicles,

burglaries etc. and offensive weapons, including sharply pointed articles.

"Reasonable suspicion" must be based on fact, rather than stereotyping such as

ethnic origin, dress, hairstyle etc. The police have guidelines advising them

to "ensure that the powers are used responsibly and sparingly" (!).

Some of these search powers (e.g. for offensive weapons and stolen

articles) can only be exercised in a public place. Others (e.g. for drugs) can

be exercised anywhere. The police can detain you, without arresting you, long

enough to carry out these searches. They are not allowed to make you undress

further than your outer coat, jacket or gloves if the search is in public. If

the police find something which they have reasonable grounds for believing is,

for example, stolen, it can be seized.

There are supposed to be some safeguards before and after searches - e.g.

the officer must, where practicable, give their name, police station and

reason for search. The officer must also prepare a record of the search and

you are entitled to a copy if you ask for it within 12 months of the search,

though not necessarily there and then.

Quite separately, the police have powers to set up road blocks and / or

stop pedestrians. If the police fear that violence is likely to take place in

a certain area, they can make an order that anyone within a given distance of

that area can be stopped and searched for offensive weapons, without any

suspicion. If they have banned trespassory assemblies in a given area, they

can turn back people en route to the assembly. The police can also set up road

blocks, not only to check for terrorist devices, but also to look out for

witnesses to, suspected of, or about to commit other serious offences.

The police can search properties, short of arrest, if they have obtained a

search warrant from a Magistrates Court. The police can enter property,

without a warrant, to arrest someone suspected of an arrestable offence, to

save life or limb, or prevent serious damage to property. They can also enter

property with the consent of the owner, or to prevent a Breach of the Peace

(see below).

When they arrest someone, the police have much wider powers. For example,

they can carry out strip searches and retain possessions found on you. They

have additional powers to enter, search and seize possessions from property

occupied or controlled by the person who has been arrested, to obtain evidence

relating to the offence or some other connected arrestable offence.

The police have extra powers when it comes to road traffic. For example,

they have the power to stop vehicles without suspicion. They can require the

production (either there and then, or within a given amount of time) of

licences, insurance documents etc. If you have any vehicles on the campaign

you may get a lot of hassle. This was a tactic much used by the police during

the Newbury campaign. Therefore, it is worth making sure that your vehicle is

totally legal if it is going to be used in connection with the campaign.

It is an offence for a driver not to give their name, address and date of

birth. It is also an offence (under Section 172 of the Road Traffic Act 1988)

for passengers not to tell police what they know about the identity of the

driver of a vehicle, if certain serious driving offences under the same Act

(eg. drunken, careless or dangerous driving) are alleged. These are important

exceptions to the "right to silence". Otherwise, passengers are not obliged to

give their names and addresses.

Legally, "driving" includes activities such as stopping to buy fuel, and

locking the car before leaving. Once you have left the car, you do not have to

give your name and address to the police, unless they believe that you have

been involved in an accident, or have committed a driving offence.

It is worth remembering that if the police are not exercising any of these

powers, you have no obligation to talk to them, give them your name or

address, assist them, remain with them, volunteer to be searched, allow them

onto your property, or give them anything which belongs to you. Having said

this, you could be charged with the general offence of obstructing the police

in the execution of their duty (see below) if you actually mislead or hinder

them in any way. There are also specific offences for failing to comply with

certain police powers. The police can use "reasonable force" to exercise their

powers.

Arrestable Offences

The official name of the offence is written first

with its common name afterwards in brackets.

Section 68 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994

("Aggravated Trespass")- To have committed this you will have trespassed

on land (not highways, footpaths or water), in the open air (i.e. not inside a

building), and actually, or with a specific intention of, disrupting or

obstructing or intimidating someone from going about their lawful activity.

This, in practice, means breaking through, or attempting to break through, a

security cordon to stop "lawful" tree felling, locking onto a machine, hunt

sabotage, basically direct action in general! It does not need a warning. Max.

sentence 3 months and / or a Level 4 fine (see below).

Section 69 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 ("Section

69") - is the offence you commit when you refuse to obey the instruction

of a cop to leave land which they believe you will commit aggravated trespass

on. They must give you a warning for this and you will have to have ignored

it, or returned within 3 months. Max. sentence 3 months and / or a Level 4

fine.

Criminal Trespass - Generally, if you are trespassing without

disrupting anything, you are not committing a criminal offence. You are

committing a civil wrong against the owner of the land and you cannot be

arrested. However, there are a few instances when it becomes criminal, for

instance, if you trespass on railway lines and restricted areas in docks and

ports.

Section 10 of the Criminal Law Act 1977 ("Section 10 - Obstructing the

Sheriff") - During evictions, this is the most likely offence you will be

arrested for. You will have to have knowingly resisted or intentionally

obstructed any person who is an officer of the court (i.e. sheriffs, bailiffs,

professional climbers) engaged in executing or enforcing a Writ. Max. sentence

6 months and / or a Level 5 fine.

Breach of the Peace or Behaviour Likely to Cause a Breach of the

Peace - This is not even a criminal offence, but a "civil wrong". It

occurs when an act is done, or threatened to be done, which either actually

harms, or is likely to harm, or puts someone in fear that it may harm, that

other person or, in their presence, their property. It must be characterised

by violence or the threat of violence. The violence can come from either the

person committing the act, or the reaction of the other person to the

behaviour of that person. However, in reality the police will arrest you for

this if they don't like the look of you, or want to find out who you are. They

may also detain you without arresting you to prevent a Breach of the Peace -

for example, by physically restraining you, or shutting you in a van.

The power of arrest comes from the Breach of the Peace Act 1361(!). It has

been retained as it is so useful to police and magistrates. It is just a

"complaint" that the police make to magistrates about you, and ask them to

uphold. So you don't even get a criminal record - you may just have a

"complaint upheld" against you. They can arrest you for this immediately, and

hold you in custody until they can take you to the magistrates. Because it is

not a criminal offence, the PACE regulations do not apply, and they cannot

impose bail conditions.

When they take you before the magistrates, they may try and do a "trial"

there and then. Because it is not a criminal charge, they do not have to prove

your guilt "beyond reasonable doubt", only on a "balance of probabilities".

You must say that you want an opportunity to prepare for a proper "trial".

They should grant you this and adjourn for another date. Again, they cannot

set bail conditions. If the complaint is upheld, the only penalty the

magistrates can give you is a bind-over (see below).

Section 1 of the Criminal Damage Act 1971 ("Criminal Damage") - This

is an arrestable offence if you, without lawful excuse, destroy or damage

(including minimal and temporary impairment of value or usefulness) any

property belonging to another, intending to destroy it. For criminal damage

costing less than £2000, the case must be tried in a Magistrates Court,

where the max. sentence is 3 months and/or a fine. If the cost of damage is

above £2000, it can be tried either by magistrates (max. sentence 6

months and/or fine), or in Crown Court (max. sentence 10 years and/or

fine).

Section 241 of the Trade Unions and Labour Relations (Consolidated) Act

1992 ("Section 241") - This law was brought in by Thatcher against the

unions, and usually refers to various forms of secondary picketing, but it is

occasionally applied to road protesters. You commit the offence by doing

certain things, with a view to compelling another person to abstain from doing

something they have a legal right to do: use violence or intimidate someone

and their family; or follow someone; or hide or deprive and hinder the use of

tools, clothes and other property; or watch and beset the person; or follow

the person with others through the streets in a disorderly manner. Max.

sentence 6 months and / or a Level 5 fine.

Section 137 of the Highways Act 1980 ("Obstructing the Highway") -

To be guilty of this you must "wilfully and without lawful excuse" obstruct a

highway. The highway is any public road, and can include a footpath. Lawfully

you can only use a highway to get from A to B, and the police decide if is a

"reasonable" obstruction. Max. sentence Level 3 fine.

Section 51 (sub section 3) of the Police Act 1964 ("obstructing the

police") - this is usually a non-arrestable offence, but may become

arrestable if a Breach of the Peace has occurred. If arrested for this,

consider suing the police (contact the solicitors in Chapter xx). You commit

the offence if you resist or wilfully obstruct a constable in the execution of

his duty. This could mean ignoring the instructions of a policeman,

deliberately misleading them, or stopping them from doing something - for

example, de-arresting other protesters, giving false details or running away

when arrested. Max. sentence 1 month prison and / or Level 3 fine.

Public Order Act 1986 lists a variety of offences which

get progressively more serious. The CJA has changed and amended this Act

slightly:

Section 5 ("disorderly conduct") - is the least serious and most

regularly used. The ingredients are that you use threatening, abusive or

insulting words or behaviour; or disorderly behaviour; or display in writing,

sign, or other visible representation which is threatening, abusive or

insulting within the hearing or sight of a person likely to be caused

harassment, alarm and distress. This is a catch-all charge which is quite

difficult to defend against, as the police do not have to produce any witness

who was upset. They just have to claim that your behaviour could have done so.

Max. sentence Level 3 fine.

Section 4a ("disorderly words and conduct with intent") - is

virtually the same as Section 5, except the police have to prove that you

intended to cause someone harassment, alarm or distress. Max. sentence 6

months and / or Level 5 fine.

Section 4 ("causing the fear of or provoking violence") - This makes

it an offence to use towards another person threatening, abusive words or

behaviour; or distribute or display any writing, sign, or visible

representation which is threatening, abusive or insulting with intent to cause

that person to believe that immediate unlawful violence will be used. Max.

sentence 6 months and / or Level 5 fine.

Section 3 ("affray") - This is committed if a person uses or

threatens unlawful violence towards another, and their conduct is such as

would cause a person of "reasonable firmness"(!) present at the scene to fear

for their personal safety. It can be tried at Magistrates Court (max. sentence

6 months and / or fine) or Crown Court (max. sentence 3 years and / or

fine).

Section 2 ("violent disorder") - This is committed where 3 or more

persons who are present together use or threaten unlawful violence, and the

conduct of them (taken together) is such as would cause a person of

"reasonable firmness" present at the scene to fear for their personal safety.

Max. sentence at Magistrates Court 6 months and / or fine; in Crown Court,

max. sentence 5 years and / or fine.

Section 1 ("riot") - an offence where 12 or more persons who are

present together use or threaten unlawful violence for a common purpose, and

their conduct (taken together) is such as would cause a person of "reasonable

firmness" present at the scene to fear for their personal safety. This charge

is very rarely used and needs the consent of the Director of Public

Prosecutions. Max. sentence 10 years and / or fine.

There are various assault related offences, depending on who you assault

and what injury you cause:

Section 39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988 ("common assault and

battery") - is the least serious. Assault is any deliberate or reckless

act which causes a person to fear immediate unlawful violence (i.e. no actual

contact needed). Battery involves simply touching someone without their

consent or other lawful authority. Max. sentence 6 months and / or Level 3

fine for both.

Section 51 (sub section 1) of the Police Act 1964 ("assault police")

- committed if you assault a police officer or anyone assisting officer in

execution of his duty. Max. sentence 6 months and / or Level 5 fine.

Section 38 of the Offences Against the Persons Act 1861("assault with

intent to resist apprehension") - committed if you assault a cop when

being arrested. Max. sentence 2 years.

Section 47 of the Offences Against the Persons Act 1861 ("ABH") -

assault occasioning actual bodily harm involves assault causing medically

verified injuries. Max. sentence 5 years.

Sections 20 and 18 of the Offences Against the Persons Act 1861

("GBH") - two types, either simple grievous bodily harm (known as

"unlawful wounding"). The skin needs to have been broken. Max. sentence 5

years. Or "GBH with intent" to cause serious harm. Max. sentence is life.

Bear in mind other offences such as theft and burglary (especially on

offices actions) and going to equipped to commit criminal damage or to steal.

Also, be aware of (a) conspiracy, (b) incitement, (c) aiding, abetting,

counselling and procuring an offence and the principles of "joint enterprise"

- all of which can make organisers, leaflet distributors and other people

criminally responsible for the actions of others.

Levels of fines (as at 1996) are:

Level 1 - max. £200

Level 2 - max. £500

Level 3 - max. £1000

Level 4 - max. £2500

Level 5 - max. £5000

Bear in mind that these amounts are legal maximum figures, and you are

likely to actually be fined much less.

Getting Arrest ed

You'll be in very good company if you do get

arrested, and will be joining a long line of people who have been arrested for

their beliefs! However, getting arrested is not compulsory in a direct action

campaign and in fact, often it can be quite advantageous to not get nicked as

it can take you out of action and be draining. The experience of getting

arrested can be different for everyone. It can be a really good laugh,

extremely scary, empowering or isolating.

You can make it a whole lot better by knowing what to expect. In practice

often the police give warnings before they arrest because they prefer to get

you out of the way rather than go to the trouble of arresting you and taking

you to the police station. However, with most offences it makes no legal

difference if they do not warn you (exceptions Section 69 of the CJA, and

Section 5 of the Public Order Act - see above). They can always say in their

notebooks, and in court, that they warned you, even if they didn't.

If you are arrested, you should hear the words "I am arresting you for ...

[they should say an actual offence here]. You do not have to say anything, but

it may harm your defence if you do not mention, when questioned, something

which you later rely on in court. Anything you do say may be given in

evidence." It may come out as "You're nicked!" however. They do not have to

say all of the full caution if the circumstances make it impracticable. You

should be told what you have been arrested for (PACE, section 28, subsection

3). Call out to people to alert them to your arrest (you'll need witnesses)

and ask them to give their names to Action Observers or to the campaign

office. Ask the cop what you are being arrested for in front of witnesses.

You'll then be taken to a police van. You may have to wait a long while

before being taken to the station as they try and fill up the van with others,

or you may be whisked straight off. They will try and ask you loads of

questions and may even get you to fill out forms. Tell them as little as

possible - see below.

At The Police Station

When you arrive at the station you'll be led in,

possibly in handcuffs, and taken to a desk where the custody/desk sergeant

will "book you in". They will ask you loads of questions. Remember, you do not

have to give them any information - in the sense that it is not an offence.

However, it is advisable to give them your name and address as refusal will

make getting bail more difficult later on. They will often get details off you

from your possessions when you are searched. Usually people just give their

name and address. The address that you give should be verifiable or they won't

let you out. They may phone or call around at the address you give to check

it. You could demand that they recognise your protest camp / treehouse as a

proper and legitimate address.

They will try and get all sorts of other info from you, especially your

date of birth. The police national computer lists everyone by date of birth,

so if they have yours, you'll be very easy for them to trace. You will have to

decide whether you want to give them it or not. You could just politely state

that you are not legally required to give it, but this could result in a

slightly longer detention.

After this you will be "read your rights". You are entitled to see a

solicitor, have someone informed of your arrest and consult a copy of the PACE

Codes of Practice. If you don't decide to do any of these things immediately

you can change your mind later. However, you may have trouble getting the

police's attention later on, as the buzzers in the cells are often

ignored.

Tell the police (and have it recorded on your custody record) that you give

them full permission to disclose any information about your arrest to anyone

who rings up from the campaign, enquiring about you. The police have been very

unco-operative in the past and have refused to let people outside know what is

happening to arrested people, using the excuse that they are protecting the

prisoner's "privacy".

Searches and possessions

The custody sergeant decides what possessions you can keep and what should be

taken from you. The sergeant can authorise a search, including a strip search

if deemed necessary. So, do not carry things on actions that could get you

into trouble, ie. drugs or knives or sabotage tools. They can also search you

for anything which could cause injury, damage property, interfere with

evidence or assist in escape - e.g. shoelaces, belts, lighters and matches. It

is only on these grounds, or on the grounds that they might constitute

evidence, that the custody sergeant can retain clothes or personal effects.

Anything taken off you should be meticulously listed and put into a sealed bag

in your presence. You will then be asked to sign the list to say it is

correct. Check it and sign immediately under the last item so they cannot add

anything. Don't sign at all if anything on the list is incriminating.

Any search (except by a doctor) must be carried out by someone of your sex.

More intimate searches (of body orifices) can only be carried out where there

are reasonable grounds for suspecting that you have a Class A drug or have

something concealed which might cause injury.

What happens next

They will then put you in a cell. This is the boring bit. You will just have

to sit it out until they decide what to do with you. You can catch up on

sleep, read, do some stretching / meditation, or ask to have a shower. Be

aware that you may be overheard in the cell. You could create your own

entertainment! When large numbers have been arrested, it has been quite a

laugh with people singing and making music in the cells.

You can ask for a solicitor at any point during your custody. The police

must take reasonable steps to get them there as soon as possible or at least

get them on the telephone. You should be able to speak to them in private. If

you are unsure of anything, get to speak to a solicitor. All legal advice in

the police station is free whatever your financial position. You'll also be

allowed to let someone know that you have been arrested. Hopefully you'll get

to do it yourself, but you may just have to nominate someone and the police

will do it for you.

They should only hold you while they obtain evidence, and work out if they

have enough to charge you. Much depends on how serious or complicated the

allegations are. In straightforward cases, this could take just a couple of

hours, but if they have to take statements and do interviews it could take

longer... In practice, they usually hold you far longer than necessary (see

below for how to sue).

If they hold you for a long time, they should hold reviews of your

detention (called custody reviews) as set out in PACE. These should happen 6

hours after your original arrest and then every 9 hours after that. You should

be present at the review - or at the very least your solicitor should be. Make

sure that they know that you want to be present.

Interviews

They may decide to interview you in an attempt to get more evidence. If this

happens, have your solicitor present. Remember that you are NOT obliged to say

anything and that you DO still have the right to silence. The only change

since the CJA in 1994 is that if you do not mention a fact, that you later

rely on at trial, in your interview the court can draw "adverse inferences"

from this. Decide what is best for you to do, after talking to your solicitor

and co-arrestees, if possible. Be very careful that you do not drop other

people in it by what you say. Our advice is that it is nearly always best to

do a "no comment" interview. The interview is designed to help the police and

not you.

When you go into the interview room, you'll sit at a desk with one or more

cops, your solicitor and it'll all be taped. At the beginning of the

interview, it may be a good idea to say on tape something like "I am not

prepared to speak now under police interrogation, but I am prepared to defend

myself in a court of law". Some people have suggested invalidating the

interview procedure by saying "Okay! OKAY! I'll say anything, just don't hit

me anymore"!

Fingerprints, photographs and DNA samples

They may also decide to fingerprint, photograph, and take DNA samples from

you. They are only empowered to do this before you have been charged if you

have committed a serious offence. You can refuse to give your consent to

fingerprints, but they may use "minimum reasonable force" to get them. Once

they have your prints, they can always tell who you are if they arrest you

again and it is difficult to get away with giving a false name. Although it

takes a few weeks for the prints to get to their central computer, it can tell

who you are very quickly if your prints are on it already.

They may try to photograph you. You do not have to give your consent and

they are not allowed to use "minimum reasonable force" to get this. They may

ask you to sit in a chair and hold a blackboard below your face with your name

on it (like in the films!). If you refuse, they may try and take it

sneakily.

The CJA has introduced significant new police powers to accumulate and use

DNA intelligence. The police now have express powers to set up a DNA database

and to seize DNA from suspects. DNA can come from a number of sources. Firstly

there are "intimate samples" such as blood, semen, tissue fluid, urine, pubic

hair, and swabs from orifices. Secondly, there are "non-intimate samples" such

as hair samples (other than pubic hair), scrapings from under a nail, swabs

taken from parts of the body other than orifices, foot or hand impressions,

and saliva.

The rules on the police's powers depends on which type of sample they are

dealing with, whether a suspect has been charged, and how serious the charge

is. With protesters on minor charges, this is unusual, and if they do it,

they'll either pluck hair, or take saliva swabs from inside the mouth, after

charge. They can do this, using reasonable force, for "recordable" offences,

i.e. most of them.

Injuries and Doctors

If you are physically injured in any way immediately before or during arrest,

or whilst in custody (handcuff and pressure point injuries etc.) you can ask

to see a doctor. Every police station has one and they should ask if you want

to see them when they book you in. Their doctors have often been

(unsurprisingly) unsympathetic or uncooperative. They will record what they

diagnosed and how they treated it. If policemen have caused your injuries,

they will have access to the doctor's notes, and will be able to fit their

story to account for the injuries. Therefore, it may be wiser to go to a

hospital or independent doctor instead, immediately after release for a proper

report (especially if you plan to sue).

"Antecedents" form

This is a bizarre form that the police may try and get you to fill in at the

police station. They will say that this is just for the benefit of the court

to help them assess you and your position - don't believe a word of it! Since

when have the courts needed to know whether you have any tattoos? They will

pressure you into filling it out or may just ask you verbally. This form will

have all sorts of questions on it, including your schooling, employment

history, parents, health, body markings, eye colour etc. You do not have to

answer any of the questions, so don't! Anything you do say will go straight

onto the police national computer.

Juveniles

Arrested people under 17 are classed as "juvenile", and there are slightly

different procedures. The main one is that the person responsible for them

should be informed about what is happening, and that nothing should happen to

them at the police station in the absence of an "appropriate adult" (parent,

guardian, social worker).

Outcomes

There are several things that the police can finally decide to do with you.

They may release you without charge and that'll be the end of the case against

you. They often arrest, detain and release without charge to clear demos or

they may not have enough evidence. Get in touch with a good lawyer to sue (see

below).

Cautions may be offered by the police for minor offences to people who have

a minimal criminal record. The police do this to avoid the hassle, expense and

paperwork of going to court. Accepting the caution means admitting the

offence, and getting it finished there and then. It is not a criminal

conviction but will stay on your record for three years, and may be taken into

account if you get arrested again. It may be pragmatic to accept one, but it

is a convenient way for the police to settle their dubious arrests and may

make it harder to sue them later on. Think carefully and talk to a solicitor

before accepting.

If the police want to take the matter further they may release you on some

sort of bail. Bail is when you are released with an obligation to return to

the police station or to a court. Failure to return is a criminal offence

under the Bail Act. It would be harder to get bail for the original charge and

you would have a record of failing to answer bail. This may prejudice bail

applications in future.

If they need more evidence, they might release you on bail to re-appear at

the police station at a later date, where they may discontinue proceedings or

decide to charge you. Being charged means that you are formally accused of the

offence. A policeman will read out the charge against you and ask for your

reply. You do not have to say anything. Once charged you will either be bailed

to appear at the Magistrates Court, or will be held until the next sitting of

the Magistrates Court and taken before them. If the magistrates are not

convinced you'll turn up at court, or believe you'll commit further offences

on bail, or will interfere with witnesses, they can remand you in prison until

your next court case. You are less likely to get bail if the charge is very

serious.

Unless you're remanded, the police should return all your possessions. You

should get a receipt for anything they keep as evidence. Once you are out,

please phone the person you informed that you had been arrested, to let them

know.

Bail conditions

The police and magistrates have the power to impose

conditions on your bail. These conditions are usually to stay away from the

site of the protest (e.g. a 1 km or so exclusion zone), or not to disrupt any

work. Sometimes they impose a condition of residence on you - you are forced

to stay at a designated address - and they may even make you sign at a police

station daily or weekly to prove you are staying at an address. Unless

successfully challenged at the courts, these conditions will stay until you

finally go to trial, which could be several months. Bail conditions are often

strategically designed to remove you from on-the-ground action.

There are several reasons why the police impose conditions. The usual ones

are to stop you re- offending whilst awaiting trial, to prevent you causing

further damage to property / injury to self or someone else, and to make sure

that you attend court. They should not put conditions on you if their only aim

is to "inconvenience" you. You will have to sign the form giving your consent

to the conditions to enable you to leave the police station. If you refuse to

accept conditions, you will be taken before the magistrates at the earliest

available opportunity, to ask for them to set the bail conditions. This could

mean an overnight stay. In court, you will be able to argue why the conditions

are unfair.

If you break these bail conditions you can be arrested or summonsed to

court. The police will need to have evidence of you breaking your conditions

so avoid having your photo taken. The magistrates will then decide what to do

with you. They may impose harder bail conditions - bailed to live several 100

miles away for example. Or they may refuse bail, and remand you in prison or a

remand centre until your trial. The only advantage is that your trial may be

brought forward, dealt with quickly, and so you'll be free to protest again.

If you're remanded in custody and want to apply for bail, you appeal to the

Crown Court and then to the High Court. It is worth remembering that it is not

a criminal offence to break your bail conditions - it just makes getting bail

again for that offence more difficult if you are caught. It is however a

separate criminal offence (under the Bail Act) not to turn up at court to face

criminal charges.

Strategy against Bail Conditions

Bail conditions are one of the police's main weapons against activists in

sustained campaigns. Anyone arrested is put out of action or risks being

remanded. Any campaign which seeks to last a long time will have to think

before action starts about how it will deal with bail conditions, and develop

a strategy.

If given bail conditions by the police, you might get them varied by going

to see a different custody sergeant at the same station, or by applying to

magistrates. To appeal against bail conditions imposed by magistrates, you go

to the High Court. Bail conditions were challenged during the M11 protests,

when a judge agreed that the conditions were draconian, and lifted them -

freeing everyone to protest again. However, at Newbury in 1996, one man who

appealed his conditions in the High Court walked away with harsher ones! So

this option can be a bit of a gamble.

Challenging bail conditions with civil disobedience is more risky, demands

a lot of thought and lots of people to take part in it, remaining determined

and united. You can go all out and make it clear to the magistrates that you

will break any conditions imposed on you, and will carry on protesting until

they put you in prison. Make it clear that this will be what everyone does.

They may realise that it is not worth their while. This worked at Twyford Down

in 1993, backed up with a hunger strike. People at Newbury in 1996 refused

bail conditions banning them from within 1 km of the route and went on hunger

strike on remand, in prison. When it came to the Appeal in court, the

conditions were slightly eased. They were allowed to continue living at the

camps on route, but were barred from interfering with work.

These strategies were not completely effective as they included only a few

isolated, brave individuals, not a concerted effort. If hundreds of people

insisted on being taken to court over their bail conditions and then were

prepared to go on remand, their prison system might start to clog up. This

would need preparing and talking about before arrests start however. Another

strategy would be for everyone to accept them and then persistently break

them, as if they did not exist. The police would have trouble arresting

everyone. The danger with this is that they may simply film you, get the

evidence and then arrest you at another time, when you are isolated.

Support At The Police Station For Those Nicked

There are things that

people outside can do to help arrested people, for instance, making sure that

anyone who has witnessed the arrest writes a witness statement, or at the very

least leaves their contact details - especially if they are a photographer or

video user. They can inform the campaign solicitors who can push for their

release. How much contact you have with an arrested person depends on how

friendly the desk sergeant is. You should be able to get books, letters (the

police will read them), food and tobacco in. If you ask really nicely, you may

even be allowed a visit.

If the police have filled the cells in one station, or just want to be

difficult, they may take the arrested person off to a distant police station.

When the arrested person is released, the police are under no obligation to

transport them back to where they were arrested. People should try and have a

bit of money on them when they go into action for this very reason. However,

this cannot be left to chance and the campaign should try and pick people up.

This is a good, and very essential, role for people with vehicles (see "Driver

Lists" in chapter 8).

If someone has been unjustly or violently arrested, or the police behaviour

has become particularly bad, you may consider having demos at, or occupations

of, the police station. The police hate this and usually react very

forcefully. It is a very strong statement however, and can be a good way to

get the issue of police brutality or non-impartiality out. If you are being

held in the cells and you hear chants and drums outside, it can really lift

your spirits.

Preparing For Trial

If the campaign has a supportive and organised

attitude to legal matters, then preparation for trial and evidence gathering

should be very easy. The names of witnesses or their statements should have

been gathered at the time of the arrest and there should be a range of

sympathetic solicitors for people to use. Anyone arrested will hopefully have

written their own statement immediately after their arrest. In the same way

that the police can refer to their notebooks when giving evidence, you and

your witnesses can refer to any statement you made at the time of the

incident, or as soon as practicable afterwards, as long as you haven't

collaborated. This is useful, as it gives your evidence more credibility and

also means that you don't forget things.

To represent yourself or not?

You may already have instructed a solicitor and signed Legal Aid forms at the

police station. But don't assume that just because you got some advice from a

solicitor at the station that they are now representing you, and will take

care of everything. If you want them to represent you, which is especially

worthwhile for more serious charges, you'll have to formally instruct them.

Contact them as soon as you get out. The solicitor should apply for Legal Aid

as soon as possible, if you are eligible.

You may decide to represent yourself. Increasingly more and more people are

doing this, especially for political trials. There are many things that a

barrister or solicitor just cannot do and say, and this can be very

frustrating for a defendant. Many people won't be eligible for Legal Aid, but

cannot afford to, or do not wish to, spend money on a solicitor. Also, there

is a tendency for courts to refuse legal aid to political activists, so you

may be forced to represent yourself, or at the very least, do a lot of the

preparation of your case. For an excellent (and inspiring) guide to defending

yourself read How to defend yourself in court (see Chapter xx).

Evidence and Disclosure

If you have instructed a solicitor, you should have a meeting with them to

discuss your case. Your solicitor should send off for "advance disclosure"

which is a dossier of the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) case against you

(the CPS take over the case from the police). This will include all the

prosecution witness statements. If the police have a video of you being

arrested and want to show it in court, then you are entitled to see it. You

should either be sent a copy, or go and see it at the police station. If you

are representing yourself then you should do all this yourself. It is a matter

of dispute if there should be "advance disclosure" for cases which can only be

tried in the Magistrates Court, so you may face an obstinate CPS.

You will need to do your own evidence gathering too. If you are being

represented, then your solicitor should do all this under your instruction.

Make sure they do it thoroughly. Give the solicitor the addresses of any

witnesses so they should contact them to interview and prepare them for the

trial. Find any videos and photos which may help your case. If there were

Action Observers (chapter 8) present, contact them. Tell your solicitor about

anything helpful - like whether footpaths were officially closed - so they can

research this. If you want to use any photographic or video evidence, see

Filming on Actions in chapter 10.

Going to court

If you are bailed or summonsed to court, your first appearance is known as the

"plea hearing". Here you will enter your plea - guilty or not-guilty. If you

plead guilty, they may sentence you immediately. If you plead not-guilty, a

date will be set for the next court hearing (the pre-trial review). If you are

in any doubt, plead not-guilty as you can always change it later. It is more

difficult to change a guilty plea to not-guilty. If you plead guilty you get a

lesser sentence (and have to pay less prosecution costs) than if you plead not

guilty and are convicted - and you get more credit the earlier you plead

guilty!

There will also be an opportunity for you to challenge any bail conditions.

Prepare this before you go in, and present a convincing case as to why you

should not have bail conditions.

If you have never been to court before, it may be worth popping in before

your trial to listen in and get a feel for what goes on. There is always a

Public Gallery in Magistrates Courts (usually just a row of chairs along a

wall) and you are perfectly entitled to sit in. It will make you more

confident about your case.

The courts are designed to intimidate people who get sent there. The

magistrates are generally well-to-do-people from the local establishment, who

have probably been recruited at dinner parties. They usually have a

patronising attitude that they are teaching the underclass how to behave. They

have had no legal training, and will have a Clerk (usually an ex-barrister or

solicitor) to advise them on the law. There are usually three magistrates. You

may, however, especially for cases which contain a lot of technical legal

argument, get a Stipendary Magistrate (often known as a "Stipe"). These are

ex-barristers or solicitors with extensive legal knowledge. They sit by

themselves with the Clerk.

Magistrates will sit up on a platform, which is designed to make you feel

small. You will be in a defendant's box, and your solicitor (if you have one)

sits at a bench at the front on the left, with the CPS lawyer on the right.

You should ask to sit with your solicitor. Magistrates and the CPS will use

weird language and talk to you as if you know everything about the legal

system, to baffle and confuse you. Everyone in the court will have to stand up

when the magistrates enter, or face Contempt of Court proceedings. That is all

part of their "superiority". The best advice we can give is not to be

intimidated by it. The whole thing is an elaborate farce, and the magistrates

are just players in it.

After the plea, the next visit to the courts will be your pre-trial review.

This is when you, and the CPS, go through all the evidence, from each side,

discuss any disputes, and list what witnesses to call. The intention of this

is to streamline the trial and save time and expense. You should not have to

go to this if you are represented, but check first with your solicitor. You

may want to go to it anyway.

At the magistrates court a solicitor can advocate (speak), but most cannot

at a Crown Court, and have to instruct a barrister. Your solicitor may

instruct a barrister for your magistrates court case especially if they are

overloaded with cases. Barristers are usually more eloquent, but won't have an

in-depth knowledge of your case. Ask your solicitor for a "Conference"

(meeting) with your barrister before the case so you can brief them on what

you want them to say. For cases in the Magistrates court, Legal Aid won't

cover a conference, and you'll be lucky to get one.

Plea Bargaining

The CPS may try and do a deal with you. They may offer to drop a serious

charge in return for you pleading guilty to a lesser one. This is Plea

Bargaining. They usually do it just before a court case, or on the actual day

of the trial. Minor charges may be dropped in return for you accepting a bind-

over (this is not a criminal conviction - see below). They often do this to

people worried by facing serious charges. Plea bargains may be offered if they

are not confident on their chances of getting a conviction, and / or they want

to avoid expensive court cases. However, it can make your life a whole lot

easier, so make your own decisions.

The Trial

Formal trials are daunting, but the procedure is quite simple. Firstly, the

prosecution gives a brief outline of their case, and the circumstances of your

arrest. They then call their witnesses (usually the arresting officer and a

few others), and examine them, by asking them questions about their evidence,

under oath. After the prosecution has finished, your solicitor (or you, if you

represent yourself) will get the chance to cross-examine them. This is your

chance to discredit the witnesses and their evidence against you. The

prosecution then get a chance to re-examine.

After this, you or your solicitor could argue that there is no case to

answer, and invite the magistrates to throw the case out. If this is not

accepted, you will then have the opportunity to go into the witness box and

either give your case, or be examined by your solicitor. You don't have to do

this, but the magistrates may draw inferences if you don't. You will be asked

to make an oath on the bible (or other holy book), or make a non-religious

affirmation to tell the truth. Afterwards the prosecution can cross-examine

you. You can then be re-examined by your solicitor or make a further

representation yourself. Keep calm and just reiterate the facts. Your

witnesses are then called, one by one, to be examined by you, then

cross-examined by the prosecution, and then re- examined by your side.

Witnesses have to sit outside until called.

After this, your side sums up your case to the magistrates in a closing

speech. Then the magistrates will probably adjourn, returning to give the

verdict. If you win, you can apply for your costs (travel, witness costs,

accommodation etc.).

Sentencing And Penalties

Most of the things activists get arrested for

are pretty minor. You are extremely unlikely to go to prison for a first (and

second and third) offence, unless you do something serious. You are most

likely to get a small fine, and / or a bind-over and / or a conditional

discharge and / or costs of the trial. The smaller your criminal record the

lighter the penalty. With all offences, there is a maximum penalty set in

place. This gives an indication of how serious the offence is, not what you

are likely to get.

If you are found guilty, the magistrate will probably sentence you

immediately. Have your mitigation prepared. Give a brief outline of your

financial circumstances, and why the sentence should be lenient.

Absolute Discharges: This means that you still have a conviction but

no separate penalty.

Bind-overs: These are usually offered to people arrested for Breach

of the Peace. Magistrates also dole them out as a light punishment for other

offences. A Binding-Over Order is an ancient power given to magistrates and

has been left over from the Middle Ages. It is basically a promise that you

make that you "will be of good behaviour and will keep the Queen's Peace".

This really means that you promise not get arrested during a set time (usually

6 or 12 months). If you do, and get convicted, you will forfeit a sum of money

(usually around £100), although they quite often don't notice when you

break bind-overs. A bind-over stays on your record but is not itself a

criminal conviction. If you refuse to accept a bind-over, magistrates have the

power to send you to prison for up to 6 months! However, you can agree to

accept it at any time and get out of jail.

Fines: If you are fined, expect anything from £30 to

£300. Costs are usually around £30 to £100 per day in court.

It varies massively around the country, and between magistrates. If you are on

the dole or a low income, they may demand that you pay about £5 a week.

See below for info on not paying fines.

Conditional Discharges: Magistrates are quite fond of these. If you

are given one it means that if you get arrested again within a given time

(usually 6 months to 2 years), and are subsequently convicted, you may be

re-sentenced for the original offence.

Community Service and Custodial Sentences (Prison): If magistrates

or a judge are considering a Community Service Order or a custodial sentence

(sending you to prison), you should have your case adjourned for a few weeks,

for probation officers to prepare a Pre-Sentence Report. They can remand you

in custody during this time. You will be interviewed by the Probation Service

as to how much you regret your "crime", and they will prepare the report for

the judge.

Community Service means that you will be ordered to do certain tasks for

the community for a set time (20 to 240 hours). You have to consent to the

order, which is supervised by the Probation Service. If you don't do it, you

go back to court, and will probably get more hours added, or be sent to

prison. There are usually some "environmental" and outdoors jobs which you

could ask to do. You may meet some interesting people whilst doing it,

although it is not so good for women as the work teams are usually all

men.

Going to prison is a big psychological step. There is a separate section on

prison below as it is a major topic. More protesters will probably be going to

prison as things get more and more repressive.

Appeals

If you feel that your conviction and / or sentence are unjust, you can appeal.

The only problem with appealing your sentence is that the judge hearing the

appeal can actually increase it and award costs against you. You only get 21

days from the date of sentence (not conviction) to lodge your appeal, so you

should speak to a solicitor as soon as possible. You have an automatic right

of appeal from Magistrates Court to the Crown Court. The rules on Crown Court

convictions are different. From the Magistrates Court, a re-trial will take

place at the Crown Court (witnesses will be called again). If you just want to

appeal a point of law, you would appeal "by way of case stated" direct to the

Divisional Court.

Not Paying Fines

Many people decide that part of their protest is not

to pay their fines. There are several things that can happen if you refuse.

They may send the bailiffs round; they may attempt to get an Order at a higher

court to deduct money from your dole money / bank account / wages; or they may

send you to prison for a few days.

If you don't keep up with payments, you will eventually be summonsed back

to court. There, it is up to the magistrate what they do to you, depending on

what you say. If you say that you can't pay as the fine and payment rate are

too high, then they may give you another chance, and set the fine again at a

lower rate of payment. If, on the other hand, you say that you won't pay, then

they will probably send you to prison for "wilful" non-payment. If you do not

answer the summons to court, you will have a warrant issued for your arrest.

When arrested, you will probably be sent to prison unless you pay the whole

amount. Don't take money into court with you as they can take it off you.

The magistrates can do other things. They can hand the debt over to a firm

of bailiffs, whose responsibility it is to collect the debt. You will be

notified that this has happened. The court order is called a "distress

warrant". You will receive threatening letters from the bailiffs, saying that

they will call around at your property within the next few days, unless you

contact them to arrange payment. This may be all that happens, as they hope to

intimidate you into paying.

If bailiffs do call at your home, they cannot force entry. They can enter

through open doors or windows, including upstairs ones via a ladder. They can

push past you if you open the door, and are good at talking their way in. They

may ask to just use the phone; don't let them. Once they're in, you are very

compromised. They can take anything and force entry on subsequent visits. If

they take property which does not belong to you, then you have to go to court

and prove that it belongs to someone else. Speak to a solicitor, a Citizens

Advice Bureau, or the Chesterfield Law Centre (see Chapter xx) for further

information on bailiff powers.

If magistrates get an order to take money from your dole, it is taken at

source (the dole office), and you cannot do anything about it. Apparently this

takes a long time to sort out and they can only take a few pounds at a time.

The situation is probably similar for wages or bank accounts, but we're not

sure. Do not give magistrates any information about your bank account or

earnings.

If you refuse to pay and they can't get any money out of you, you will go

to prison. If you are prepared for prison this can often seem the best option.

Currently, if your fine, plus court costs, total less than £200 you will

be sentenced to 7 days. If your fine and costs total above £200 then you

should get 14 days. You would only serve half of your sentence - see below.

Prison

It is likely that some people in your campaign may end up in

prison. Although most of the things that protesters get arrested for carry

quite small penalties, if you refuse to pay fines, or refuse to accept their

patronising bind-overs and outrageous bail conditions, or break injunctions,

you will probably end up in prison.

Quite often people will expect to go to prison and be prepared. However, it

can occasionally be a complete surprise for some people who have accumulated

lots of charges, or are falsely accused of serious things, or if they get a

harsh sentence from a particularly vile magistrate. Whatever, when people go

to prison they need support.

Some people cope very well in prison and learn a lot from it. Others hate

the experience and take a long time to recover. This depends on individual

experiences inside. Take time to prepare yourself, think about what prison

will mean, and how you will psychologically cope.

Not everyone ends up in prison, but it is worth knowing something about it,

as the fear of the unknown is one of its most intimidating aspects. There is a

long history of civil disobedience throughout the world. In Britain at the

moment the penalties are pretty minor. If you take nonviolent direct action in

many places you "disappear". While we have the opportunity to take action, we

should do all we can. Prison is just about the British State's hardest legal

sanction; by overcoming fear of it, you can be truly free.

There is a lot of information to include in this section. We cannot go into

all the detail here, but there are some excellent organisations set up to help

people inside (see Chapter 16). There are many different types of prison

(men's, women's, young offenders', remand centres, open, secure etc). We

include just basic information which should be relevant to most prisons.

Before the court case:

If you think there is a possibility of being sent to jail, don't hope for the